Fond Memories of Aluoi

As the team members set the demolition charges around the camp that would level or collapse every bunker and building on Aluoi, I walked around the camp and as I walked among familiar surroundings, my mind wandered back to some of the fun times we had these past months.

I remembered when I first arrived at Aluoi, as I stepped off the helicopter and entered the Camp; I had spotted a 105 howitzer along with a young Vietnamese artillery lieutenant and his gun crew. When I was first introduced to him, he seemed depressed and sad; however, the moment he saw the artillery insignia on my fatigues, his eyes lit up and I could not get him to stop talking as he excitedly went on and on (in almost fluent English) about how happy he was to see another artillery officer and what he and his crew—and his 105 howitzer—could do for the camp.

The previous Special Forces officer at Aluoi was a Chemical Corps officer who knew little or nothing about the artillery. According to the Vietnamese artillery officer, he would not let him fire the weapon. It didn’t take long for me to ask the young Vietnamese artillery lieutenant to position his 105 howitzer on the high ground in the center of the camp.

I asked him to elevate the tube of the weapon one or two degrees above the horizontal—just enough to clear the buildings in the camp—and set the fuse timer on the ammunition to “zero time.” After he had set up the weapon, I asked him to fire a few rounds across the perimeter wall encircling the camp. His eyes lit up as he realized what I wanted to do. Both of us knew a fuse setting of “zero time” on a 105 howitzer round, would mean the round coming out of the barrel would be “bore safe.”

“Bore safe” on the 105 howitzer ammunition meant the round would not explode until it had travelled at least fifty meters from the muzzle of the weapon. That distance would carry the round over the perimeter wall beyond the killing radius of its explosion. That safety feature was built into every 105 artillery fuse to keep young GIs from blowing themselves up because they forgot to set the fuse before firing the weapon.

When I asked the artillery lieutenant if he had any white phosphorous (WP) ammunition, he became even more excited. He said he had plenty of it. We had warned everyone in the camp to either get down below the wall or back away to the center of the camp to watch our warning to the NVA and VC we knew were observing our every move from their mountain hideouts.

For the next twenty minutes, the young artillery officer and his crew—rotating the 105 howitzer in a 360 degree circle—fired WP artillery shells over the perimeter wall around the perimeter of the camp. The rounds exploded about forty meters beyond the wall in a beautiful white mushroom cloud of phosphorous smoke.

If the NVA or VC were watching us from their hideouts up in the mountains, I was certain those White Phosphorous explosions had caught their eye and struck fear in their hearts as well. They knew—as well as we did—that phosphorous on human flesh burns through the skin, flesh and bone until you cut off its supply of oxygen by putting a pack of mud on the wound or submerging the wound into some body of water.

Sadly, several weeks later, the artillery lieutenant received orders to move his 105 howitzer and crew back to Da Nang for further movement.

His artillery unit was being moved to the Mekong Delta area as part of a build-up against an anticipated attack on Saigon. I have often wondered what became of that young lieutenant after the communists took over the country.

As I walked past the side of our old command bunker, approaching the entrance, I looked down into the outside kitchen where our two “political prisoners”—our cooks—had prepared the team’s daily meals. The “kitchen” was not much more than a foxhole-sized room cut down into the side of the bunker. The stove was wood fired and more often than not, the “cooks” singed or downright burned the main course. This was the only place in the world I have ever eaten burned scrambled eggs.

I should explain that two of our political prisoners were teenage sons of a university professor in Da Nang who had been speaking out about the military Junta ruling South Vietnam at the time. The government had put the professor in jail in Da Nang and sent his two teenage sons to Aluoi for “Political Indoctrination.” They were both energetic and happy kids and extremely intelligent—they also spoke fluent English. While I was not married at the time, it was like having two frisky teenage sons around.

I remember seeing the younger one scrounging around the communications bunker garbage can one day, asking if he could have the empty commo wire reel they were throwing away. A few days later, I saw him pushing a homemade wheelbarrow around the camp wearing a huge grin—as I looked on in amazement at his ingenuity.

The two of them went around camp listening to their small, hand-held, battery-operated radios playing Vietnamese music—to the satisfaction of the CIDG Soldiers. I asked one of the sergeants where they got the batteries from and he laughed and said, “From us.”

We used military PRC-25 field radios to talk to each other while on patrol. We also used them to make contact with any U.S. Army, Air Force, or Australian aircraft in the area as well. The radios required a battery about the size of an old Calc I or physics textbook. When the batteries got low, we could not risk having them go out on us while on patrol, so we would replace them and then discard the dead—or unusable—batteries.

However, these two young “Einsteins” figured out that some of the battery cells were still usable and they would take apart the “dead” battery we had discarded as unusable and—using a two-wire contraption that had a flashlight bulb on the end—they would probe the hundreds of individual cells that made up the core of the entire battery.

Whenever they found individual cells that would make the bulb light up, they would cut out those “good” cells from the core of the battery until they had enough of them to run their small radios. While the overall strength of the entire battery was not enough to run a PRC-25 radio, there were enough good usable individual cells—inside the batteries’ core—to power their small radios.

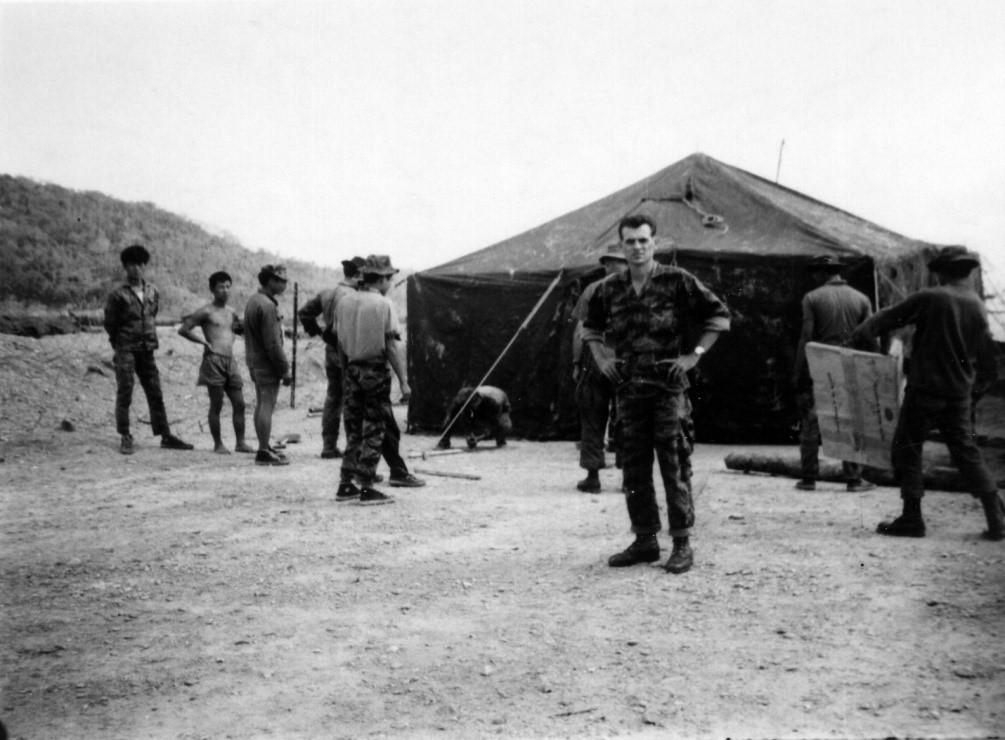

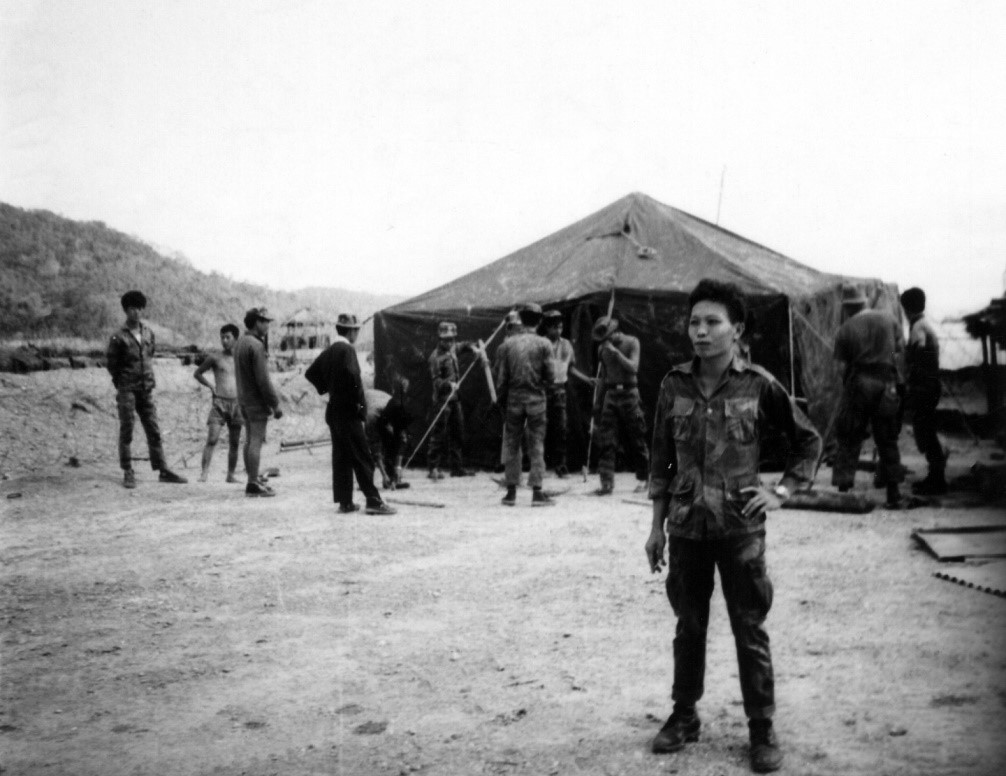

Leaving the “kitchen,” I stood at the entrance to the bunker and looked out over where we had often played volleyball. Believe it or not, the Montagnards were the camp champions—beating even our team. And how could I forget our celebrating one of the sergeant’s birthdays? We had put up an old Korean War era canvas tent on the volleyball field right next to our bunker and had planned on a special dinner that evening—hopefully one not burned.

As I recall, one of the sergeants produced some fine homemade moonshine from a still he had allegedly made for that day.

I found out later that day—after several lips had been loosened from drinking the product—that the still had been made months before I got there. It had been hidden inside the communications bunker.

To ensure our combat readiness, I made certain that half of the NCOs and one of the two Aussies did not drink any of the homemade concoction; however, it soon became evident Bushy had a few sips too many. It was also apparent he was “soused” when he got up from the ammo crate he was sitting on—mumbled something about “this stuff had no kick at all,” thenpromptly tried to walk through the side wall of the tent—several times in a row! Mumbling something about “who in the hell closed the door.”

Bushy finally fell through the tear he had created in the wall of the old tent. Remembering my bout with Harry Hardgrave’s moonshine several decades earlier on “Smoke Bomb Hill” at Fort Bragg—I was very glad I had wisely chosen to drink coffee. As I turned and entered the command bunker—for the last time—I looked around the dark musty room remembering the first night I had slept there.

•••

When I had first arrived at the detachment, the Communications Sergeant told me to put up my mosquito netting around my bunk. “It’s not for the mosquitos, Sir, it’s for the rats,” he had told me.

I vividly recallthe first evening I slept in the bunker. I had put my package of Marlboro cigarettes on an empty ammo crate next to my bunk just outside the netting. Sometime in the middle of the night I was awakened to a strange sound like someone scraping a shovel in hard dirt.

I quietly grabbed my .45 caliber pistol and turned slowly toward the noise to see this huge rat sitting up on its hind feet holding my cardboard box of Marlboro cigarettes in its front paws. Sitting up on its hind legs, the rat was about eight or nine inches tall and about three inches across at the chest. It was bigger than any squirrel I had ever seen.

The rat had taken a cigarette out of the box and was sitting there chewing on—almost inhaling—the paper and tobacco. When it reached the filter, it spit it out and reached down for the box, opened the lid and took another cigarette out and repeated the process. There were already several filters lying on the ammo crate.

I reached over to whack it upside the head with the pistol, but when I moved the netting trying to strike him, the rat had already disappeared. From that night on, everything went inside the netting to include the empty ammo crate—and my Marlboros.

•••

Leaving the command bunker I walked to the front of the camp, and with the help of the CIDG Camp Commander, I lowered the Vietnamese flag. It was time to go! I folded the flag and handed it to the CIDG Camp Commander. We then walked together out through the huge main gate of the camp—the one we had recently built out of PSP (perforated steel planking).

As I walked across the runway towards the waiting helicopter, I heard the all too familiar sound of unusual guitar music. I looked over to see the two boys sitting down near the aircraft that was to take them to freedom. The boys were strumming on their homemade guitars. The two boys had fashioned the strings for their guitars—using individual strands of our commo wire.

They had meticulously stripped and separated the different strands of the wire apart to make the different thicknesses of the guitar strings—and therefore the varying sounds on their guitars. Perhaps it would be more accurate if I described their homemade guitars as sounding a little more like “out-of-tune” ukuleles.

I had asked General Walt when he visited the camp several weeks earlier—if they decided to close the camp—could I release the two boys to go home to their mother. After a very brief meeting with them that day he had agreed I could quietly let them return home to their mother in Da Nang.

The new XO from Ashau arrived by helicopter to take the CIDG troops and Nungs remaining at Aluoi down the valley to Ashau along with several of the SF personnel. Both of the Australian Warrant Officers, the Montagnards, and several of the SF sergeants all had returned to Da Nang on a C-130 earlier that morning.

I had been told I was to return to Da Nang after overseeing the destruction of the camp. Colonel McKean told me he had a special mission for me before I was to return stateside—he did not say what it was and I did not press him knowing if he wanted me to know, he would have told me over the radio.

As the last C-130 carrying the remaining CIDG forces was getting ready to take off, the two boys ran over and asked me if they were going to Ashau with the soldiers. Before I could answer them, I felt the ground shake; and I turned to watch the camp go up in a cloud of smoke. Multiple explosions told me we had successfully done our job. Detachment A-102a was no more.

Turning back to look at the two boys clutching their homemade guitars, I smiled and told them they were to fly back to Da Nang with me. After we were airborne, circling the billowing smoke that was once Detachment A-102a, I told the boys when we arrived at Da Nang, a military sedan would pick them up and take them to be put in the same prison where their father was.

What I did not tell them was the driver of that sedan was a civilian Vietnamese member of one of the U.S. Army Special Forces Operational Teams. His orders were to drive them to where their mother lived in Da Nang with instructions to tell them—as he pulled up to their home—they were now free.

I left Vietnam shortly after arriving in Nha Trang and unfortunately, I never got to see the two boys again. I do not remember their names. And like the children we pulled from the burning buildings—and rescued from the exploding bombs in Nha Trang earlier in the year—I have never heard what happened to them since then.

We all now know the conflict lasted for another decade. We also know some newsman as well as a few historians have painted the U.S. Vietnam era soldier as a pot-smoking, drug-using hippie, yet during the thirteen years the U.S. military were fighting in Vietnam, there were more than nine million Americans who served on active duty of which just over six million were volunteers. During this same period of time, more than 97 percent of these service members were honorably discharged.

During the thirteen years of that conflict—from 1961 to 1973—there were more than 58,000 U.S. military personnel killed and more than 200,000 wounded. Today, there remain more than 1600 service members still unaccounted for—Missing In Action (MIA).

Except for a handful of U.S. Marines guarding the US Embassy in Saigon, the last US military combat units had left Vietnam two years earlier in 1973. There were no U.S. combat troops in Vietnam when the U.S. Embassy fell to the North Vietnamese Communist forces two years later on April 30, 1975.

I can only hope that before the North Vietnamese Communists took over the entire country, the two boys who had been at my SF Detachment—and the children we pulled from the burning buildings in Nha Trang—all had a chance to grow up to live full and happy lives, hopefully in some other country, free from communism.