The Berlin Encounter

I left Rome that Sunday afternoon by train for Frankfurt, hoping that when I got to Frankfurt, the weather would have cleared and I could get a military hop to West Berlin—which at that time was only the western half of the city of Berlin. The Soviets occupied the eastern half of the city. This division was the reason for how the terms East and West Berlin came about

After WWII, the western half of the city of Berlin was divided by the victorious Allies into three parts—the French, British and American Sectors. These three sectors were adjacent to the Soviet controlled eastern half of the city. What made access to the city even more difficult, was the fact that the entire city of Berlin was surrounded by what was then known as the Soviet Zone—often referred to as East Germany

To stop the emigration of East Berlin citizens to West Berlin, the Soviets had erected a huge concrete wall across the eastern border of West Berlin—clearly dividing the Eastern Soviet Sector from the American, British and French Sectors of West Berlin. What came to be known as the “Berlin Wall” had been completed several years earlier, but there was still a chance I could get to see East Berlin—still occupied by the Russians—because the Allied Forces had just opened a new checkpoint. The new checkpoint was located at Friedrichstrasse in West Berlin, at the wall on the border with East Berlin. The checkpoint was named Checkpoint Charlie.

Checkpoint Charlie was added as the third crossing point into East Berlin from the American Sector. However, German civilians could not cross into East Berlin through that checkpoint. It was for use by Allied military, and State Department personnel.

The other two crossings for West Berliners (Checkpoints Alpha and Bravo) had just reopened—several days earlier— allowing West Berlin citizens to again visit East Berlin for the first time since August of 1961.

Arriving in Frankfurt, I was informed by the army specialist at the standby flight desk that the only way I could catch a hop into West Berlin was to sign on as a classified courier. There was a daily C–47 flight into West Berlin early every morning and they always needed a classified courier. I had a Top Secret clearance that could easily be validated by a telephone call to the Special Forces Security Office back at Fort Bragg.

My clearance was authenticated that afternoon by a priority military TWX (today’s equivalent of an email). I was handed a classified instruction manual to read and authenticate before I was certified as a courier. I read the manual explaining the emergency procedures for handling and disposing of classified material should the plane go down over Russian-occupied German territory.

Among the detailed instructions, the procedures required that I be the last person to board the plane after the classified materials were loaded into the cargo hold. I was also to be the first to disembark from the aircraft when it landed at Tempelhof Airport in West Berlin to ensure no one had access to the documents while the plane was on the ground.

If the airplane were forced down by enemy aircraft and required to land in Russian-occupied East Germany, my instructions were clear—I was to immediately exit the aircraft and destroy the classified documents on board using the thermite grenades I would be given. This was, I thought, assuming I would not be shot by the Russians as I left the aircraft. The instructions were specific.

The mail bags containing the classified documents would be placed in the cargo hold of the aircraft under us, inaccessible from inside the aircraft. At the time, I remember also reading there would be U.S. Air Force jet fighters accompanying us along the flight corridor while we were flying over occupied East Germany. The primary mission of these fighter aircraft was to drop aluminum foil ahead and behind our courier flight to confuse the enemy radar below us on the ground. Their secondary mission was to provide us with air cover should we go down in East German territory.

The next morning as instructed, I appeared at the terminal several hours before the scheduled departure time. I was introduced to the Army major in charge of the classified documents. I have no recollection of his name, but years later, in watching an episode of M*A*S*H, I thought I had seen his twin brother when I first laid eyes on Major Burns—old “Ferret Face.” This Major’s idiotic mannerisms and facial expressions were identical to those of Major Burns.

The Major instructed me there would be two mail bags of classified documents put on board the aircraft by his people after everyone had boarded the aircraft and it had taxied out on the edge of the runway. After the bags were loaded into the cargo hold of the C–47 (under the fuselage), I would board the aircraft and keep my eye on the cargo door under the aircraft until the aircraft started moving down the runway. I was then to swing back into the aircraft and, with the assistance of the crew chief, close the door located behind the wing, forward of the tail section.

The Major became noticeably irritated when I questioned this procedure. I asked him why he could not just drive down the runway in his sedan alongside or behind the aircraft and watch the door from his moving vehicle.

I could not envision anyone running after a moving C–47 and attempting to steal several heavy bags of mail from it. “These procedures are to be followed to the letter!” he barked. “There will be no deviation!”

He then had me sign for two sealed, serial-numbered bags of classified documents. I asked to verify the inventory of the contents and—you guessed it—the procedures did not require an inventory of the bags’ contents. The major then had me sign for the .45 caliber pistol, a holster and belt, and four thermite grenades.

As I boarded the aircraft, I noticed that there were about a dozen military passengers—and they were all field grade officers, mostly full colonels. There were also several men in civilian clothes who I assumed were either State Department or CIA. The plane began taxiing towards the runway. I put down my duffle bag and briefcase and turned towards the open door of the aircraft.

My paratrooper experience helped me survive the somewhat strange experience that followed. The airplane was now on the runway and beginning to pick up speed as it started its take-off run. Before sticking my head out the door, I had removed my beret, tie, and khaki shirt knowing the blast from the propellers would rip off my beret, parachute wings, and military ribbons—and anything else that would catch the prop blast. As the airplane lifted off the runway, I closed and latched the door.

The instructions stated that after the plane had leveled off and began its flight down the corridor, I was to brief the passengers. So, I put my shirt and tie back on, picked up the intercom mike and addressed the passengers. I asked them who had eaten a large breakfast and they all looked at me like I was crazy! Two or three raised their hands.

“That’s good,” I said. “Because if we are forced down in enemy territory, you will all have to assist me in eating the two bags full of classified documents we put aboard just before takeoff.”

They all started laughing and one of the colonels said something about my solution made more sense than the instructions he had read on disposing of the documents. He was an Air Force Colonel, and later when I sat down next to him, he told me that I was lucky it was not raining when they took off. He said the propellers would have blown all of the runway water into my face as I hung outside the door. Spotting my Master Parachute badge, he then added “But then you already knew that.”

The flight to West Berlin was uneventful. Several times along the corridor, I looked out the window and saw the accompanying jet fighter aircraft pass by us. It was a strange feeling. We were flying over communist-occupied East Germany.

After we landed at Tempelhof Airbase, I signed over the bags of classified documents, turned in the pistol, belt, and four thermite grenades and was officially relieved of my courier duties. I headed for a nice clean, quiet hotel—and a good German restaurant.

The next morning, I got up, put on my uniform and beret and went down to Checkpoint Charlie. It was not a very inspiring sight. Checkpoint Charlie was a small wooden shanty that was painted white. It looked like a portable hamburger stand similar to those we had seen on the street corner in Chicago outside Wrigley Field or Comisky Park. The white wooden shack was surrounded by sandbags and as you approached it, you could see the East German police (Volkspolizie or VOLPOs for short) just yards away from the building on the East German side.

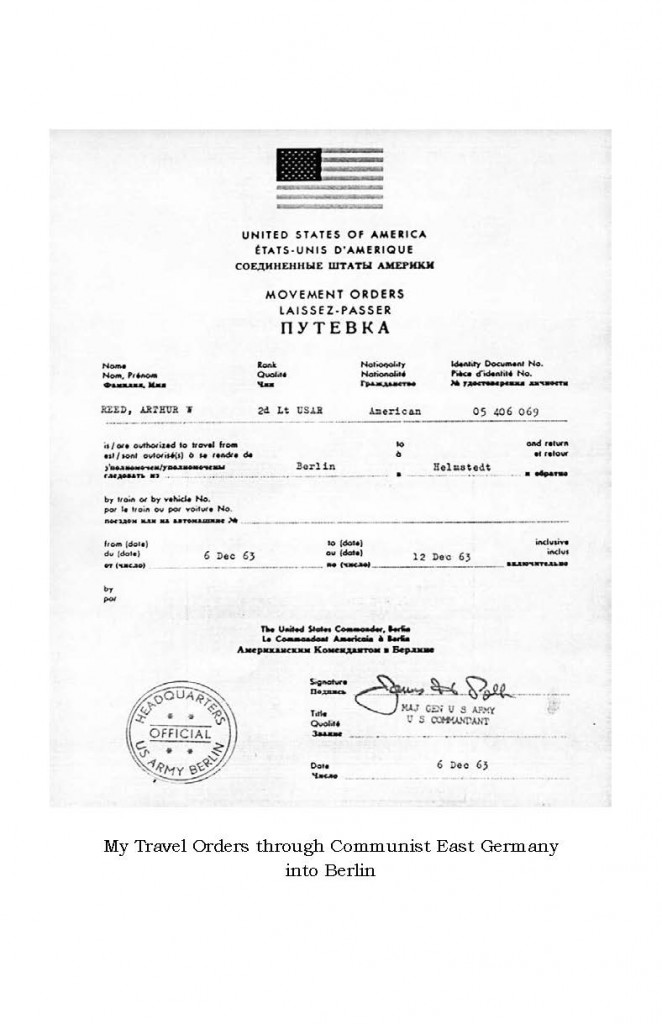

I approached the open window of the shack and asked if I could visit East Berlin. The army corporal said, “Yessir” and then asked to see my ID card and my travel orders. In order to visit East Berlin, my travel orders had to authorize me to be in East Berlin. I gave him a copy of my leave orders and my ID card and he handed me a briefing document that among other things told me I had to return through this same checkpoint.

The document also warned me not to throw gum wrappers, cigarette butts, or paper on the ground or to spit on the street or sidewalk while in East Berlin. It also told informed me I could exchange and spend no more than twenty dollars in U.S. currency for East Berlin Deutsche Marks, which was not a recognized currency in West Germany.

The corporal handed back my ID card and travel orders and asked me to sign my name, rank, and serial number—and the time of entry into East Berlin—on the register affixed to the clipboard he handed me. I asked the guard why we had to record the time. He told me if I did not sign back out through the Checkpoint Charlie within four hours, they would come looking for me. “Great,” I thought, as I proceeded towards the East Berlin wall. “How would they know where to look for me?”

As I walked towards the East German VOLPOs, a black sedan with several passengers in civilian clothing inside drove slowly passed me and proceeded through what resembled a rat maze of street barriers designed to prevent any vehicle from speeding through the checkpoint. The VOLPOs stopped the car, checked the occupants’ ID cards and then waived them on. As I approached the VOLPOs, I remembered the briefing booklet had cautioned me that I was not to show them any ID card if they asked.

I was to state that I was an American military officer. I did not speak to them and they did not salute me. I was aware that the VOLPOs were not really military soldiers; they were East German police—and as such they were civilians.

By now the black sedan had already cleared the Russian checkpoint just ahead. I kept walking towards the next barrier, which was manned by two armed Russian soldiers. They stood ramrod straight and saluted me as I approached them. I returned their salute and in impeccable English they asked to see my ID card.

I replied that I was an American military officer and did not need to show any ID while in uniform. They then handed me a clipboard and said I had to sign in. Again, I repeated that as an American military officer, I did not need to do so. They waived me on and saluted me again. I returned their salute and walked into East Berlin. As I passed the two Russian soldiers and entered East Berlin itself, I noticed a short rather plain looking—somewhat frumpy-looking woman—about fifty years old.

She was wearing a black skirt that went almost to her ankles and a thick brown wool sweater. Her shoes resembled the kind of white shoes worn by hospital nurses back then—the ones with the wide toe and thick heels—except these shoes were black. She was carrying a large black bag on her left shoulder and as I passed her, she looked straight at me, but I appeared to not even notice her as I walked by her.

As I walked along the street, I stopped in several shop windows and noticed in the reflection of the glass that she was right behind me. As I proceeded down the main street further into East Berlin, she remained always about twenty to thirty feet behind me. “How strange,” I thought, “I’m being followed.”

Looking around, I noticed the distinct difference between what I had seen in the free sector of West Berlin and this Russian occupied sector of East Berlin. East Berliners wore drab, dark clothing and there was little or no automobile traffic on the streets. As I passed the East Berliners on the street, they would not look me in the eye—they always glanced away as I approached them. They did not appear to be very happy at all. In West Berlin, however, the people wore bright colors and the street traffic was like downtown Chicago. The people on the street would smile and greet you as you passed them. They would look at you—they were happy—and it showed!

Something else caught my eye as I proceeded down the street further and further into occupied East Berlin. The two East German VOLPOs at the first checkpoint were short and squatty looking, and they had no weapons. But the Russian soldiers I passed were all armed with AK-47 automatic rifles—with fixed bayonets. And they were all six feet or taller—and sharply dressed.

They walked the streets or drove jeeps riding in pairs—you never saw a Russian soldier by himself. They saluted me smartly as I approached them. And yes—I returned their salute just as smartly as I passed them. I turned around once and observed they had kept on walking. They did not turn to look at me.

I spotted a German bank and went in to exchange my twenty-dollar bill for some unknown amount of East German Deutsche Marks. My lady friend followed me into the bank and went to another line in front of another teller’s cage.

There were three or four people in front of me so I had to stand in line for a few minutes. No one looked at me or spoke to me.

As I approached the metal bars on the teller’s cage, I said in my best German that I wanted to exchange twenty dollars in American money for East German Deutsche Marks. The teller smiled and answered me in fluent English.

Looking through the bars on the teller’s cage waiting for her to make the exchange, my peripheral vision caught two men coming up alongside of me—one on each side—and the one on the right slid something in front of me on the teller’s counter at the window.

All of my intelligence training suddenly came into focus. “If you look down it may say follow me, you’re under arrest,” I thought. So I kept my head ramrod straight and looked straight forward straining my peripheral vision until I could make out a tall, white-haired man on my right with a goatee and a short, dark-haired man with a mustache and goatee to my left, both dressed like college professors in the States.

I strained my eyes to look down without moving my head and saw part of a news clipping that the man on the right had slipped in front of me. I could read the large print of the headline. It was printed in English. It announced that President Kennedy had been assassinated. The man standing to my right—in fluent English—said, “This is such a sad time for all Germans!” He paused. “We are all so sorry to hear this.”

I had read in the Army newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, and heard on the U.S. Radio Station in Frankfurt that President Kennedy had been assassinated a week earlier in Dallas. Suddenly, I remembered that President Kennedy had just visited West Berlin a few months earlier in June.

Perhaps these two men were genuine in their expression of sympathy. But then, perhaps this was a setup!

** END OF CHAPTER PREVIEW **