“The Rest of the Story . . .”

My father was twenty-two years old when he received his induction notice from the local draft board in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on April 22, 1918 (Order #651, Serial #356, Division #4). He was ordered to report to the draft board one week later on April 29, 1918, for immediate induction into the United States Army.

Immediately after his induction, he was shipped to Camp Davis, Texas, for training and deployment with the 358th Infantry of the 90th Infantry Division. In less than two months, he would be on a troop ship headed overseas to the War in France. Less than five months from the day he was inducted, he would find himself in battle near the small French village of St. Mihiel.

The 90th Infantry Division was activated on August 25, 1917 at Camp Travis, Texas. It was nicknamed the “Alamo Division” and sometimes referred to by the enlisted men as the “Tough Ombres” (for Texas and Oklahoma). Initial members of the 90th Division came from Texas and Oklahoma; however, just before the division deployed to France in the summer of 1918, it received a large number of new recruits from other states like Minnesota. The division began its embarkation from Hoboken, New Jersey, in early June of 1918, and by June 30 all of the units of the 90th Infantry Division had sailed from Hoboken. The division initially landed in England where, on July 4, 1918, the 358th Infantry (including my father) paraded before the Lord Mayor of Liverpool.

That evening, the entire 358th Infantry was hosted at a banquet given by the city of Liverpool, England. Shortly thereafter, the 358th departed Liverpool, England, and arrived in France where they were stationed at Minot, France.

In early September, the unit was moved about 300 km east of Paris to a small village in the northeast part of France. The name of the village was “Villers–en-Haye.” In 1918, the small town had a population of only 96 people. In 2010 the population of “Villers–en–Haye” was still only 167.

My dad’s unit’s first engagement with the German Army came on September 12, 1918, at a town called St. Mihiel. The town had a population in 1918 of slightly more than 2000 residents. It was located 42 km from the town of “Villers–en-Haye” on the edge of the Meuse River. The town had grown around a Benedictine Abbey founded in 709 A.D. At the time of the battle, there were still several of the Abbey buildings, which had been constructed in the 17th and 18th century, standing in the town.

The town’s church had a hand-carved wooden door dating back to Roman times. Both the church and the Abby buildings are still there today, undamaged by the fierce fighting there more than ninety-five years earlier. In 2010, the population of St. Mihiel had grown to only 4,816.

The World War I battle that took place at St. Mihiel on September 12 – 14, 1918, was the first major American military offensive of the war. The campaign against the German fortifications there involved 550,000 men of the U.S. First Army commanded by Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. The 90th Infantry Division (including my father’s Regiment) was part of that force.

Because their three-day campaign, led by the U.S. First Army, was a successful one, they forced the Germans to relinquish a military fortification held since 1914. However, in those first three days of battle in mid-September of 1918, the 90th Infantry Division suffered a total of 37 officers and 1,042 enlisted men killed in action.

Another 266 officers and 8,022 enlisted men were wounded and mustard gassed by the Germans during the battle. In just three days, the division had lost more than half of its men! Private John William Reed, Company F, 358th Infantry, was among those soldiers who were wounded and mustard gassed by the Germans that first day of battle, on September 12, 1918.

Today, more than 4,150 American soldiers, killed in that September offensive, are buried in the American Military Cemetery at St. Mihiel.

Now—for the “Rest of the Story . . . . . !”

It was now more than half a century since Dad had fought and was wounded on the battlefields near Verdun. I had already received reassignment orders to St. Louis, Missouri, and I was getting ready to leave Europe—having had a brief opportunity to visit those battlefields. Judy wanted to make one last visit to see Ilse Ludecke, the world famous German doll maker who lived in Schwetzingen. She wanted to visit her and buy more of her dolls before we left Germany.

While Judy visited with the doll maker, I practiced my German by conversing with Ilse’s older sister. After I mentioned that my father had fought in France during World War I, she laughed and said that I was too young to have a father who was in the First World War.

“Mein Vater diente im Ersten Weltkrieg” – “My father served in the First World War,” she said.

“Sie sind gerade ein Baby. Sie sind zu jung, um einen Vater zu haben, der in diesem Krieg.” – “You are just a baby. You are too young to have a father who was in that war.”

I then told her that my father had fought near Verdun at St. Mihiel, France, in September of 1918 and that he was wounded and mustard gassed by the opposing German forces in that battle.

She stared at me and momentarily looked somewhat confused, and then she excused herself and went upstairs, returning shortly clutching a scroll. She handed me the scroll and asked me to read it.

As I unrolled the scroll and began reading it (mentally translating the German words into English), I could not believe what I was reading. It was a certificate addressed to Oberst (Colonel) Ludecke, Kommandant (Commander) of the 81st Chemical Brigade for a special mission against the American 90th Infantry Division in September of 1918.

It was signed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, and dated in October of 1918. Without thinking, I turned to her and said, “Your father killed my father!” She turned pale and appeared weak-kneed.

I quickly put my arm around her shoulders and, realizing the ramifications of what I had just blurted out, I said to her “But he knew enough to marry my mother who was German.” I then told her my mother’s parents were born in the small town of Möhringen just on the outskirts of Stuttgart. She looked at me and laughed.

“Sie sind nicht deutsch, Sie sind Swaibish” – “You are not German, you are Swaibish,” she said.

I should mention at this time that the Swaibish are known as a hard-headed (or bull-headed) clan of Germans living in the Stuttgart area of Germany (including the town of Möhringen). She said something to her sister, Ilse, and they laughed about the “Swaibish” connection.

Then the two of them invited my wife and me to accompany them upstairs to their home above the store. I learned later when speaking with one of the neighbors that Ilse Ludecke and her sister had never before invited Americans upstairs to their home.

As we came up the stairway and entered the large living room, I noticed there were paintings of military officers lining one wall.

Judging by the uniforms worn by each of the men in the paintings, I saw that most of the uniforms pre-dated World War I. The older sister pointed to the painting of her father and grandfather as well as one of her great-grandfather, telling me that all were once officers in the Prussian Army.

She explained when the American soldiers came through their town during WWII, she and her sister would take the military paintings down and hide them in the closet. When the American soldiers left, they would return the paintings to the wall.

Frau Ludecke walked over to a closet behind a beautiful ornate wood burning stove and returned with a small brown cardboard box. She opened the box and showed me a large piece of shrapnel from a WWI mustard gas shell. The shell fragment was about nine inches in length, and had some bombed-out buildings painted on its surface.

She explained her father did not want to be in the military, that he always wanted to be an artist. He had brought home this painting he had made depicting a battle scene near Verdun. Painted on the side of this large piece of shrapnel was a scene from one of the small French villages that her father’s unit had shelled.

Frau Ludecke explained while the mustard gas had eventually killed my father from his wounds on the battlefield that day in France, her father also died of cancer just a few short years after returning from the war.

She believed her father’s cancer had developed from him mixing the chemicals and handling the mustard gas mortar rounds just as sure as she believed those mustard gas shells her father had fired upon the American soldiers during the St. Mihiel campaign had caused them to later die of cancer.

We chatted for a while longer and as we left, Ilse’s sister gave me a hug and said to me, “Ihr Vater machte eine kluge Wahl, welcher feiner Sohn, den er hat.” – “Your father made a wise choice, what a fine son he has.”

Several weeks later, my family and I left Germany for stateside, and several months later the handmade dolls my wife had ordered arrived at our home. I thought one of the doll boxes was a bit heavy and after opening the box and removing the doll, I noticed a second small brown cardboard box at the bottom.

Upon opening the box, I noticed the note on top. It read “Besser haben Sie das als wir” – “Better you have this than us.” Inside was the piece of shrapnel she had showed me that day. It was the one her father had picked up on the battlefield and upon which he had painted a portrait of the French village he had shelled and where my father was wounded that September day in 1918.

Below is a photo of that WWI mustard gas shell fragment.

Dad was medically discharged from the U.S. Army in January of 1919. He spent the next several decades going from one Veteran’s hospital to another, courageously fighting the deadly effects of the cancer caused by the mustard gas.

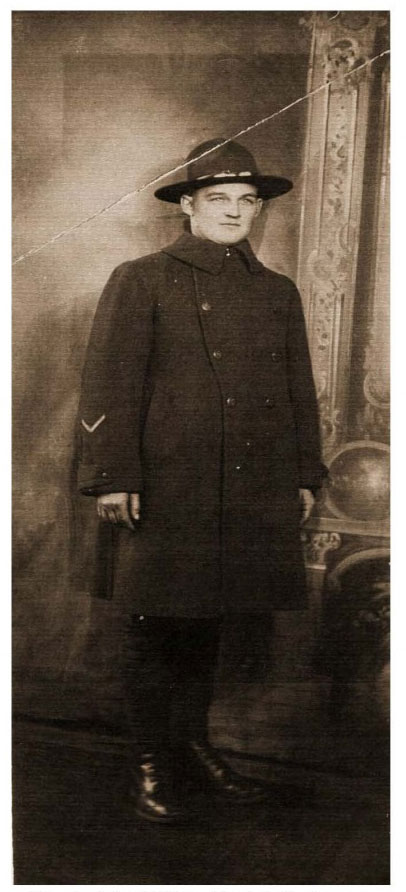

Dad died in 1945 at the Hines Veterans’ Hospital, located just outside Chicago in Hines, Illinois. As a young boy, seeing a picture of my father in his WWI “Doughboy” uniform, I always thought he had sewn his Private First Class stripe on upside down. However, later as a young soldier, I learned the “V” sewn on the right sleeve of his uniform was a WWI “Wound” insignia.

During the summer of the anniversary of our country’s two hundred years of independence, brother Bob sent his son over to Heidelberg to visit as a HS graduation gift. I was able to take my nephew “Scotty” with me on a trip I had already planned through some of the battlefields in France where my father (his grandfather) had fought in WWI. We also got a chance to visit some of the WWII battlefields as well—including the Normandy beachheads and Pointe-du-Hoc.

It was Bastille Day in France (July 14) and in one of the small villages we passed through that morning—going from Verdun to Paris—we came upon a small group of WWI and WWII veterans forming up to march in their local village’s parade that morning. When they found out I was an American officer and a former paratrooper from the 101st Airborne—and that my father had fought alongside the French near Verdun in WWI—they excitedly asked me to march with them.

Later that night, we stopped at a huge gathering of French citizens on the outskirts of Paris who had gathered in some bleachers for an outdoor concert.

We stayed to hear the music and after the concert ended—and we were all waiting for the fireworks display—Scotty and I—to kill time—got out the Frisbee and ended up entertaining several thousand French citizens.

Judging from the crowd’s oooh’s and aaah’s, and the cheers and applause we received playing in front of the bleacher crowd that night, it seemed the “Frisbee” was still unknown—and previously unseen—by many of the people in the crowd.

The following summer, brother Bob sent his daughter Kim to visit. Judy, Molly, Cathy and I took Kim to London—including a wild ride across the English Channel on the Hover-Craft. Kim had another wild ride a week later when I drove her to the airport in Frankfurt for her flight home. That trip involves a 100+ mph ride on the autobahn alongside an unmarked van filled with Russian soldiers changing into civilian clothing and illegally travelling on the autobahn in Western Germany. But I will let her tell that story.

Private John William Reed, Infantryman

Company F, 358th Infantry

90th Infantry Division

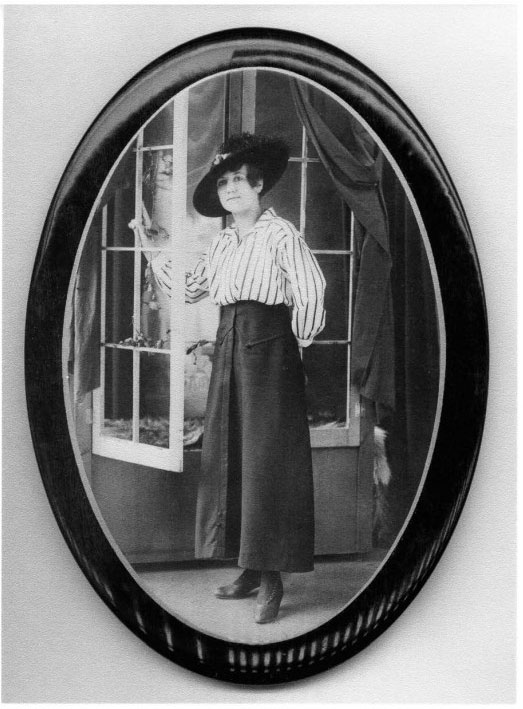

A photo of what Dad saw in 1931 when he first met Mom.

They were married in 1932 at Christ Lutheran Church

in Oak Park, Illinois.

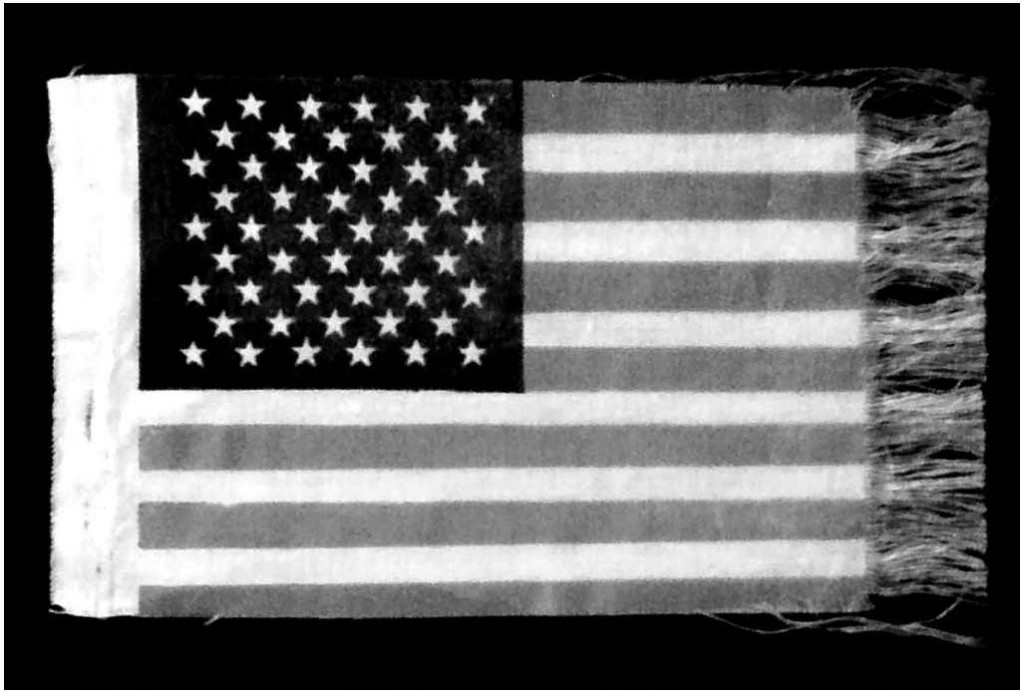

On July 4, 1976, this Flag accompanied Major Arthur W. Reed and his nephew Scott Reed on a 3,167 mile, fourteen day journey, from Heidelberg, Germany, through Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. It flew over the Normandy beaches at the Sword, Juno, Omaha and Utah beachheads, and again at the United States Army Ranger’s beachhead at Pointe-du-Hoc on the north end of the Normandy beaches. At Sainte-Mere-Eglise it paid its respects to the men of the 101st Airborne Division who gave their lives in liberating the town that day in 1944. It stopped to honor the French and American war dead at Saint Lamont and also at Verdun in the Argonne-Meuse area where Scott’s grandfather had fought and was wounded in World War I.

The flag flew from the antenna of the car we drove during those fourteen days. I had the flag, along with this inscription, mounted in a frame. My nephew Scotty Reed now has the framed flag and inscription.